The third book by Ljubica Buba Miljković, entitled “On Serbian Art, with Love”, which contains collected scientific papers and essays, is published posthumously. The third volume has been edited by Vesna Bašić because Ljubica Miljković sadly passed away on 26th May 2025.

The first volume was published in 2024, while the second and the third have been published this year, since 2025 is the “year of Saint Sava”, in which the Serbian people and the Serbian Orthodox Church celebrate the 850th birth anniversary of Rastko Nemanjić – Saint Sava. Since the editorial board of the Foundation “For Serbian People and State” has opted for a three-volume book because of the length, content, synthesis of knowledge, expertise, quality and merits of this review of Serbian art of the 20th century, we are now presenting you the third book by Ljubica Miljković.

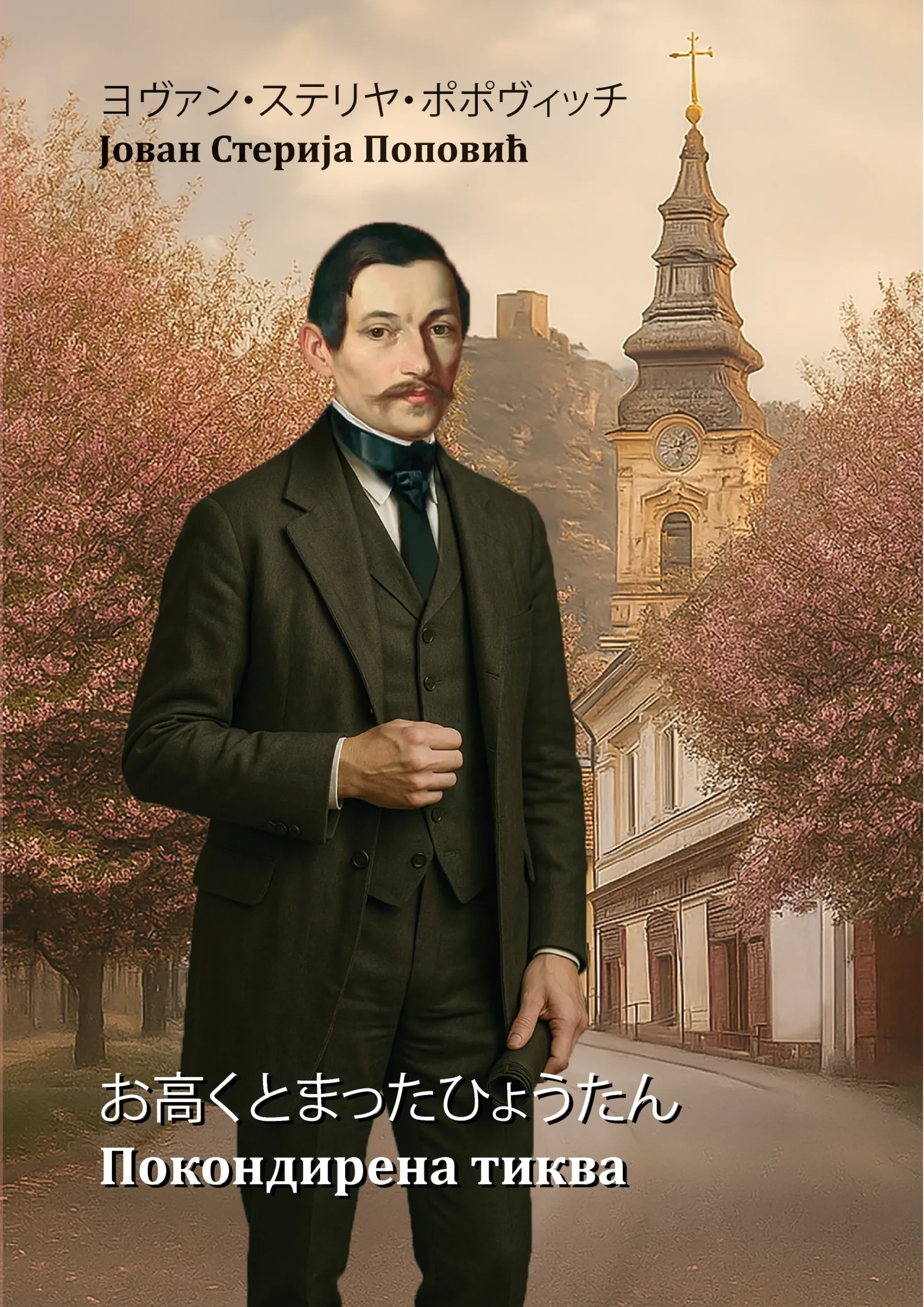

I am both proud and honoured by the role of the editor of this book because Jovan Sterija Popovićn was born in my birthplace. Vršac is called “the largest Japanese town in the Republic of Serbia” because it has hosted the largest number of artists and athletes from Japan in the past decade. Our wish is to have Sterija’s works live in Japan both through literature and theatre, “on the boards that mean life”. The writer combined literary genius, particularly in comedy, with influential activities in the development of education, culture and institutions in Serbia. “Pokondirena tikva” is a comedy depicting the character of a woman who publicly tries to pass herself off as high class, but her “tate-mae” (artificial image) has nothing to do with her “hone” (honest thought). This discrepancy between what we want to be and what we are is explained by the Japanese concept “tate-mae vs hone”. In modern society, through his universal comedy of character, Sterija makes us laugh and wonder: Who are we really when we take off our masks ?”

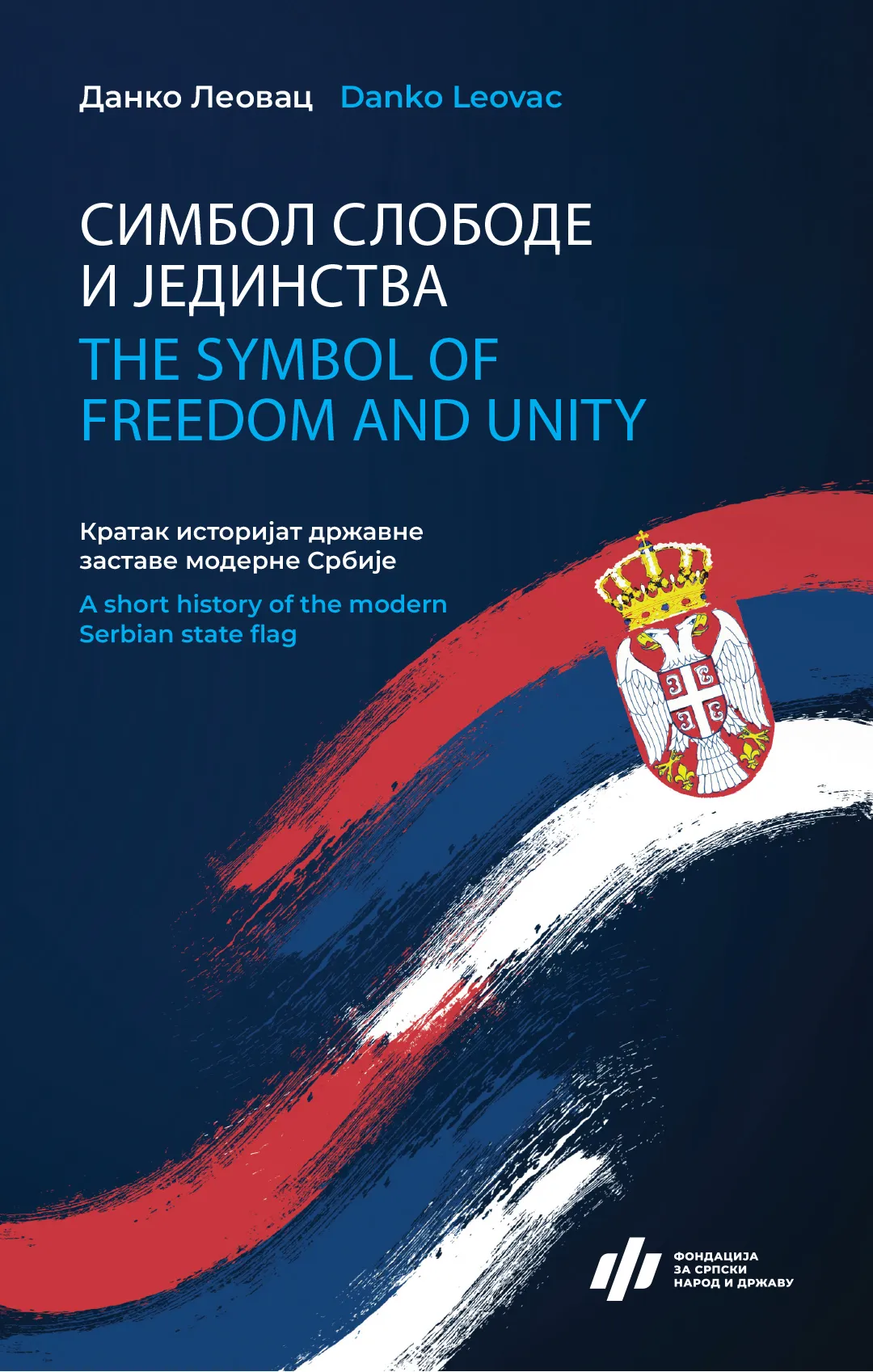

Flags stand for an integral part of human civilisation since certain decorative elements have been used to represent various symbols of particular identity and as a means of communication. The history of flags shows creativity and adaptability of humankind in terms of the use of visual design in order to express various collective values, and additionally to indicate their permanent significance in different cultures and eras.

The very issue of characterology and the mentality of a people requires multidisciplinary approach, encompassing all scientific fields that have a connection with it, as the classic of our characterology, Vladimir Dvorniković, forcefully points out. Thus, this bibliographic list of works provides a very rich directory of the most prominent Serbian scientists who, from their own perspective, dealt with the characterology and mentality of their people.

When the young Miodrag Đurić aka Dado settled, around 1952, in the garret of the house of his maternal aunt Vukica Milosavljević, aka Vule, in Strahinjića Bana Street in Belgrade, he had already rebelled, breaking from the socialist realism imposed on him at the Fine Arts School of Herceg-Novi (1948–1952), where his maternal uncle, Mirko Kujačić, who had taken him in at the death of his mother in January 1945 year

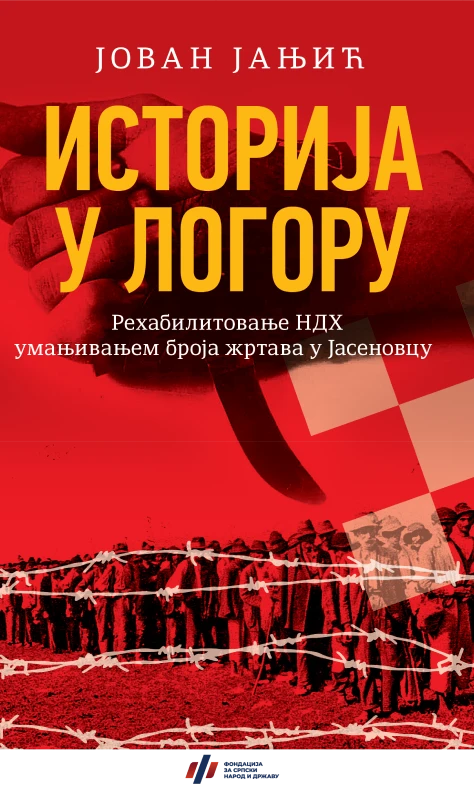

The word “camp” refers to restricted freedom, imprisonment, the power of the one who runs the camp over the one who is imprisoned in it, coercive control of the victim, abuse, killing… Just as people are imprisoned and taken to the camp, the powerful ones in the world try to “imprison” history by exercising violence over people in order to change their minds, and equality there is violence against history in order to alter it…